|

The

fortnight from Christmas Eve to Twelfth Day (Epiphany, January 6) was

the longest holiday of the year, when, as in a description of

twelfth-century London, "every man's house, as also their parish

churches, was decked with holly, ivy, bay, and whatsoever the season of

the year afforded to be green." Villagers owed extra rents, in the form

of bread, eggs, and hens for the lord's table, but were excused from

work obligations for the fortnight and on some manors were treated to a

Christmas dinner in the hall.

This

Christmas bonus often reflected status. A manor of Wells Cathedral had

the tradition of of extending invitations to two peasants, one a large

landholder, the other a small one. The first was treated to dinner for

himself and two friends and served "as much beer as they will drink in

the day," beef and bacon with mustard, a chicken stew, and a cheese,

and provided with two candles to burn one after the other "while they

sit and drink." The poorer peasant had to bring his own cloth, cup, and

trencher, but could take away "all that is left on his own cloth, and

he shall have for himself and his neighbors one wastel [loaf] cut in

three for the ancient Christmas game to be played with the said

wastel." The game was evidently a version of "king of the bean," in

which a bean was hidden in a cake or loaf, and the person who found it

became king of the feast. On some Glastonbury Abbey manors, tenants

brought firewood and their own dishes, mugs, and napkins; received

bread, soup, beer and two kinds of meat; and could sit drinking in the

manor house after dinner. In the village of Elton the manorial servants

had special rations, which in 1311 amounted to four geese and three

hens.

|

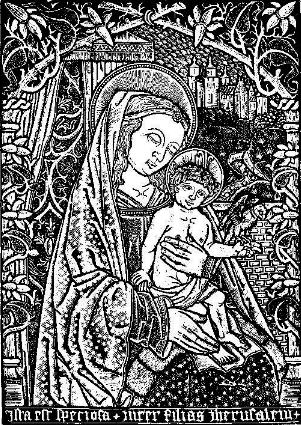

The Virgin &

Child

|

In

some villages, the first Monday after Epiphany was celebrated by the

women as Rock (distaff) Monday and by the men as Plow Monday, sometimes

featuring a plow race. In 1291 in the Nottingham village of Carlton, a

jury testified that it was an ancient custom for the lord and the

rector and every free man of the village to report with his plow to a

certain field that was common to "the whole community of the said

village" after sunrise on "the morrow after Epiphany" and "as many

ridges as he can cut with one furrow in each ridge, so many may he sow

in the year, if he please, without asking for license."

Excerpts from: Life in a

Medieval Village by Frances & Joseph Gies. New York:

HarperCollins Publishers, 1990.

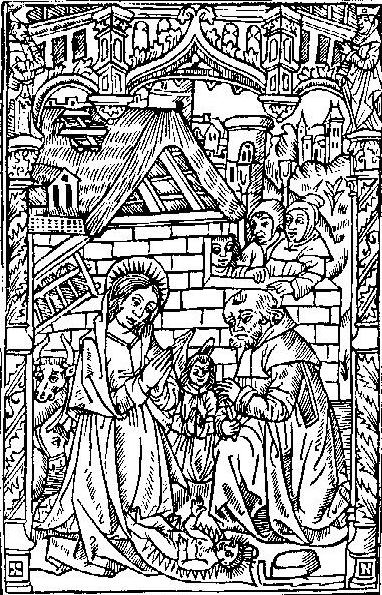

The Nativity, from Horae, London

(Pynson), about

1497

|

Besides conviviality, carol singing,

and entertainments, the Christmas holidays brought a suspension of

everyday standards of behavior and status. On the eve of St. Nicholas'

Day (December 6), the cathedrals chose "boy bishops" who presided over

services on the Feast of the Holy Innocents (December 28), assisted by

schoolboys and choirboys. On January 1, in the Feast of Fools, priests

and clerks wore masks at mass, sang "wanton songs," censed with smoke

from the soles of old shoes, and ate sausages before the altar. During

the boisterous Christmas season the lord often appointed a special

force of watchmen for the twelve nights in anticipation of rioting.

Tenants on a manor belonging to St. Paul's cathedral, London, were

bound to watch at the manor house from Christmas to Twelfth Day, their

pay "a good fire in the hall, one white loaf, one cooked dish, and a

gallon of ale [per day]."

On Christmas Eve the Yule log was brought

in - a giant section of tree

trunk which filled the hearth, and was kept burning throughout the

twelve nights.

At the upper end of the scale, baron and

king entertained their knights

and household with a feast and with gifts of "robes" (outfits

comprising tunic, surcoat, and mantle) and jewels.

All over Europe the twelve days of

Christmas brought the appearance of

the mummers, bands of masked pantomimists who paraded the streets and

visited houses to dance and dice. In England, plays accompanied the

mumming.

New Year's, like

Christmas, was an

occasion for gift giving, and Mathew Paris noted that in 1249 Henry III

exacted from London citizens "one by one, the first gifts, which the

people are accustomed superstitiously to call New Year's gifts." "First

gifts" were omens of success for the coing year. So was the first

person who entered the house after midnight, the "first-foot," who

determined the fortunes of the family for the year. In some places this

portentous visitor had to be a dark-complexioned man or boy, in others

light-haired, while elsewhere it was considered desirable for him to be

flat-footed.

|

Excerpts from: Life in a

Medieval Castle by Joseph and Francis

Gies. New York: Harper & Row Publishers, Inc., 1974.

|

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()