![]()

![]()

![]()

Part 2. The Franklin and the Cook; Feasting in Chaucer's Poetry

![]()

![]()

One of the longer food descriptions in the Tales occurs during the Franklin's introduction in the prologue:

A Frankelyn was in his companye;/A Franklin was in his company;

Whyt was his berd, as is the dayesye./White was his beard, as the daisy.

Of his complexioun he was sangwyn./Of his complexion he was ruddy.

Wel loved he by the morwe a sop in wyn./Well loved he in the morning a sop in wine.

To liven in delyt was ever his wone,/To live in delight was ever his wont,

for he was Epicurus owne sone,/For he was Epicurus' own son,

That heeld opinioun, that pleyn delyt/Who held the theory, that complete delight

Was verraily felicitee paryft./Was verily perfect felicity.

A householder, and that a greet, was he;/A householder, and a great one, was he;

Seint Julian he was in his contree./Saint Julian he was in his country.

His breed, his ale, was alwey after oon;/His bread, his ale, were always equally good;

A bettre envyned man was no-wher noon./A more envied man was nowhere found.

With-oute bake mete was never his hous,/Without meat pie was never his house,

Of fish and flesh, and that so plenteous,/Of fish and flesh, and that so plenteous,

It snewed in his hous of mete and drinke,/It snowed in his house of meat and drink,

Of alle deyntes that men could thinke./Of all dainties that one could think of.

After the sondry seasons of the yeer,/According to the various seasons of the year,

So chaunged he his mete and his soper./He varied his meat and his supper.

Ful many a fat partrich hadde he in mewe,/Full many a fat partridge he had in coop,

And many a breem and many a luce in stewe./And many a bream and many a pike in pond.

Wo was his cook, but-if his sauce were/Woe to his cook, unless his sauces were

Poynaunt and sharp, and redy al his gere./Poignant and sharp, and ready all his carvers.

His table dormant in his halle alway/His table stationed in the hall always

Stood redy covered al the longe day./Stood ready set all the day long.

A "table dormant," filled with food

The Franklin's wealth and fondness for well-prepared food is reminiscent of another famous 14th c. literary figure, the Goodman of Paris, whose advice to his young bride survives today as Le Menagier de Paris, one of the best examples of medieval domestic duties and cookery.

The cook, Roger Hodge, also called Hodge of Ware, was actually based on a real London cook known to Chaucer, a Roger Ware. (Hodge was a nickname of Roger). Chaucer obviously intended for his London readers to recognize this poor cook with the sore on his knee. Although his introduction in the Tales is not as long as the Franklin's, it is just as rich in the mention of food and prepared dishes:

A Cook they hadde with hem for the nones,/A Cook they had with them for the occasion,

To boille the chicknes with the mary-bones,/To boil the chickens with the marrow-bones,

And poudre-marchant tart, and galingale./And tart flavoring, and spice.

Wel coude he knowe a draughte of London ale./Well

could he appreciate a draught of  London

ale.

London

ale.

He coulde roste, and sethe, and broille, and frye,/He could roast, and boil, and broil, and fry,

Maken mortreux, and wel bake a pye./Make stew, and well bake a pie.

But greet harm was it, as it thoughte me,/But a great pity was it, as I thought,

That on his shine a mormal hadde he;/That on his shin a bad sore had he;

For blankmanger, that made he with the beste./As for blancmange, that he made with the best.

A contemporary portrait of Roger Hodge

Another description of his abilities occurs in the Cook's prologue to his tale, but is far from complimentary. The host of the pilgrimage accuses Roger of not only selling warmed over and stale pasties, but of having so many flies in his shop that they often end up in the food. His poor, stubble-fed geese were so badly prepared that the host tells him, "From many a pilgrim hast thou Christ's curse."

Cooks are also featured in an unsavory manner in The Pardoner's Tale. After a long discourse on the sin of Gluttony, we read:

Thise cooks, how they stampe, and streyne, and grinde,/Those cooks, how they pound, and strain, and grind,

And turnen substance in-to accident,/And turn substance into accident,

To fulfille al thy likerous talent!/To fulfill all your greedy appetites!

Out of the harde bones knokke they/Out of the hard bones they knock

The Mary, for they caste noght a-wey/The marrow, for they throw nothing away

That may go thurgh the golet softe and swote;/That may go through the gullet soft and sweet;

Of spicerye, of leef, and bark, and rote/Of spices, of leaf and bark and root

Shal been his sauce y-maked by delyt,/Shall his delicious sauce be made,

To make him yet a newer appetyt./To provide him with a newer appetite.

![]()

![]()

| Feasts are mentioned several times throughout Chaucer's

writings,

including the seldom discussed Troilus and Criseyde. But as

stated

previously, these are all very brief and seldom include descriptive

scenes

helpful to modern cooks.

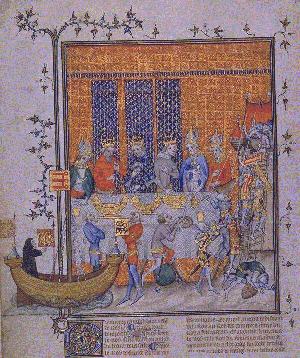

An elaborate banquet featuring a pantomimic siege is described in The Franklin's Tale: "For often at feasts, I have heard told, that magicians within a large hall, have made appear water and a barge, and made it sail up and down the hall. Sometimes there seemed to appear a fierce lion; and sometimes flowers sprang up as in a meadow; sometimes a vine and white and red grapes; sometimes a castle made of stone and mortar; and when they pleased made it disappear." Such spectacles, designed for the entertainment of feasters, were common during Chaucer's period. On January 6, 1378, Charles the V of France entertained the Emperor Charles IV in the Royal palace of Paris with a pantomime representing the arrival of the Crusaders and the capture of Jerusalem in 1099. |

Charles V's famed pantomime for the Emperor |

![]()

A Chaucerian Cookery continues with:

Book I. A Chaucerian Cookery

Part 3.

Chaucer's

Foods

© James L. Matterer

Return to: Table of Contents

Book I. A Chaucerian Cookery Part 1